The Green Sheet Online Edition

March 3, 2025 • 25:03:01

The promise, challenges and unanswered questions of CBDC - Part 1

This is the first in a two-part series exploring Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC): what it is, why central banks are considering it and the challenges it presents. For some, money makes the world go round; for others, Money? It's a crime; but we can all probably agree that money can't buy you love. You probably recognize popular song lyrics in this article's opening lines. While songwriters may find the topic a source of contrasting inspiration, either way, money matters.

Anyone with a rudimentary knowledge of macroeconomics knows that money goes beyond the notes and coins we – still – have in our pocket, (M0 in economic jargon).

The digital money we spend with a credit card performs exactly the same function as a euro note, a dollar bill or a pound note: it is a means of exchange, a unit of account and a store of value, all of which combine into what the 19th century economist William Jevons called a "standard of deferred payment" or put simply, an accepted way to settle a debt.

But this digital money wasn't exactly issued by the central bank, (so it gets another name, M1) and should you decide to put some of it into a deposit account it gets called something different again, (M2 or M3—exact definitions can vary from country to country). Already we can see that money is something of a movable feast. This taxonomy of money is useful because it shows that "money" is not just one thing, but different depending on its usage.

So why do we need another type of money? What can a central bank digital currency do that existing digital money can't, and why are some central banks getting excited about them (in so far as central banks convey excitement), while others have abandoned the idea altogether?

What purpose does a CBDC fulfill?

Perhaps the easiest way to understand what CBDC can do is to see its use as identical to paper money, only money in a digital form.

When governments (or back in the day kings), reserved themselves a monopoly on minting money, it was for good reason: they earned revenue from it, (seigniorage); it ensured that the thing they called "money" was the same everywhere (no counterfeiting); and there was an understanding that it was important not to have too much of the stuff – which is why they eventually tied it to something rare and hard to get: gold.

Central banks see an opportunity to do the same with digital currency. (The conditional is important here. While the functioning of cash is similar in almost every jurisdiction, and while the international payment schemes—Visa, Mastercard—bring a degree of homogeneity and standardization in all their markets, a standard definition of CBDC remains to emerge).

A well-designed CBDC would aim to replicate all the attributes of cash but in a digital format:

- instant value transfer (when you pay with cash, ownership immediately changes hands – a CBDC could enable this same instant, direct transfer digitally;

- privacy - cash transactions are intrinsically private—neither the payer's source of funds nor what the recipient does with the funds unless they are deposited in a bank is known to either party. A CBDC could mimic this feature to the extent that government decides it should do so.

While instant transferability of value is feasible and uncontroversial, will governments really allow total privacy and untraceability in a digital currency? Unlikely, and already a significant divergence from what has made cash king for so long.

But instant transferability of value with a CBDC is significantly different from existing instant payments, (or fast payments), as we know them today, which still usually rely on a bank network to process the transaction and subsequently to store it.

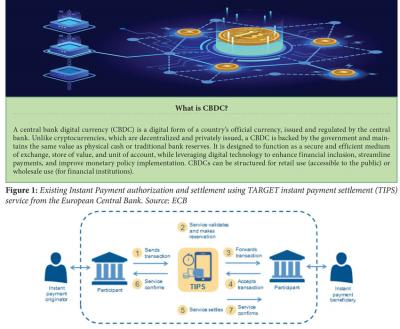

Today, if I want to send a friend in Belgium money, I can do it "instantly" from my bank account in Paris to his bank account (with a German neo-bank) and he can spend the funds in Brussels in less than 10 minutes using a Visa or Mastercard (see Figure 1). This uses the Eurosystem TIPS infrastructure, which, without getting into the technicalities of it, ultimately relies on a conventional banking model.

See Figure 1: Existing Instant Payment authorization and settlement using TARGET instant payment settlement (TIPS) service from the European Central Bank. Source: ECB

With a CBDC, the money would go directly from my wallet in Paris to his wallet in Brussels, bypassing any bank settlement processes. Then, when it comes time to spend the money, that process too would be a direct transfer of digital currency from the buyer to the seller, (who could then, for traceability purposes, be obliged to deposit the money—instantly—in a standard bank account). Conceptually, these are very different processes to what occurs today, but neither central banks nor retail banks are setting out to disrupt the existing banking ecosystem.

In the second and final article in this series, we'll examine the practical challenges of implementing a CBDC, different models proposed by central banks and whether digital currency truly solves existing financial problems.

Mark Dillon is solutions marketing director at Ingenico, https://ingenico.com/us-en, a global leader in payment acceptance and service with advanced integrated solutions and a network of partnerships that simplify the world of payments and bring value added services to move commerce forward. Contact Mark on LinkedIn at linkedin.com/in/markodillon.

Notice to readers: These are archived articles. Contact information, links and other details may be out of date. We regret any inconvenience.